could have also titled this post "L'enfer c'est nous "(Hell's us). Hell does not exist, at least as conceived by the Catholic dogma: the place of punishment where the souls of sinners are condemned to death, to eternal torment and suffering. In another post talk, maybe (or maybe not), the history of the concept of Hell in the West, because it is a curious invention of some parents of the Catholic Church, with counterfeiting and shameless manipulation of the biblical texts.

But now I want to dwell on a philosophical and literary topics: the assumption that there is Hell, yes, but not underground or anywhere after the death of men but here (on earth) and now (while living). We are the ones that we forge our own Hell ( L'enfer, c'est nous ), encouraging attitudes, thoughts and feelings that make us suffer, and also built the Hell for others, when we make them puñeta (and thus I said Jean Paul Sartre : L'enfer, c'est les autres ). In the novel

The Impatient Alchemist (2000), Lorenzo Silva of , researchers are questioning an individual, Clench Ochaita, suspected of murder. Ochaita actually innocent of the murder he is charged, and is also suffering a disease in its terminal stage (as in the novel dies shortly after this dialog):

"Look, Sergeant Ochaita spoke again, still face. I do not know how much I have left. I do not know if they will be fifteen days, or ten, or two. I have not had a bad life been good, I come with mine many times and I was able to see that many never get whims. But now it blows me [...] Moreover, if you had killed someone, now give me the pleasure to confess. Not that I do not believe in hell. Go do believe: I lived there. So I do not care what I expected. After all, this is like coming home .

What is the pedigree of this design classic ? Lucretius in Rome sought to disseminate Epicurean philosophy, under the guise of didactic poetry: he wrote a beautiful poem De rerum natura , on which we have mentioned more than once in this blog . One of the tenets of Epicurean philosophy is that Hell does not exist, among other reasons, because the souls of men did not survive the death of people. In a long passage in Book III (lines 978-1023), Lucretius argues that conventional punishment of Hell (those Tántalo, Ticio, las Dánaides) en realidad son metáforas de los sufrimientos que experimentamos en vida, fruto de nuestros vicios morales. He aquí algunos versos (978-983, 992-997):

Atque ea ni mirum quae cumque Acherunte profundo

prodita sunt esse, in vita sunt omnia nobis.

nec miser inpendens magnum timet aëre saxum

Tantalus, ut famast, cassa formidine torpens;

sed magis in vita divom metus urget inanis

mortalis casumque timent quem cuique ferat fors. [...]

sed Tityos nobis hic est, in amore iacentem

quem volucres lacerant atque exest anxius angor

aut alia quavis scindunt cuppedine curae.

Sisyphus in vita quoque nobis ante oculos est, qui petere a populo

saevasque fasces et semper Secures

imbibit tristisque recedit Victus.

And few doubt that the deep Acheron

punishment conveys the legend, all are in life. Tantalus

There is unfortunate that the huge rock theme

suspended in the air, as told, nothing paralyzed by terror;

but in life, the vain fear overwhelms

gods to mortals, and fear the perils to which each, will send you the chance.

Actually, for us Tityus is he who, overcome by love,

lacerate the vultures and recommend an anxious distress,

or we tear the troubles of any other passion. Sisyphus

there too, but in life and before our eyes:

is get the people who crave the beams and superb axes,

always defeated and withdrawn and sulky. Lope de Vega

held on the same topic in Sonnet 54 of his book human Rhymes (1609). Clearly following Lucretius, Lope compares legendary convicted of Hell (Danaides, Tantalus, Ixion, Sisyphus, Prometheus) with the intimate suffering caused by the jealousy of love

That forty-nine forever seeking to drain the lake

Averno;

Tantalus water and young tree

never try glass or apples;

suffered during the axle of your wheel moves

Ixion, for eternal time;

Sisyphus, crying in hell,

the hard edge of the mountain bears;

to pay the crazy warning

Prometheus being a thief of divine calling,

in the Caucasus, their arms linked;

terrible penalties are, but suddenly

see another lover in the arms of his mistress,

if they are older, who saw the tell.

Quevedo also believes that it is suffering in life, Hell of love in his heart: "My heart is a realm of terror."

EXAGGERATION Persevere in

YOUR LOVE AND AFFECTION IN EXCESS OF HIS SUFFERING

In the cloisters of the soul lies quiet

wound, but hungry

consume life in my veins feeds

widespread calls for the marrow. Bebe

hydropic my life burning, ash

already emaciated and loving, beautiful fire

body, holds its light

in smoke and darkness.

flee people, and am horrified by the day;

extend in long black voices crying, silent sea

that my burning pain sends.

A voice cries I gave the song,

l'confusion floods my soul: my heart is

reign of terror.

I have even a hypothesis about where particular read Lope de Vega and Quevedo the text of Lucretius: surely in one of the anthologies or miscellanies of Latin texts that were so successful during the sixteenth century, in which the extracts were encompassed under headings that represent topics and motives. The topics, in turn, were organized in alphabetical order. A likely candidate would be the book Illustrium poetarum flowers, Mirándula Octavian. He met many issues. A jewel of my library is a copy of this book, in 1553, whose cover is this:

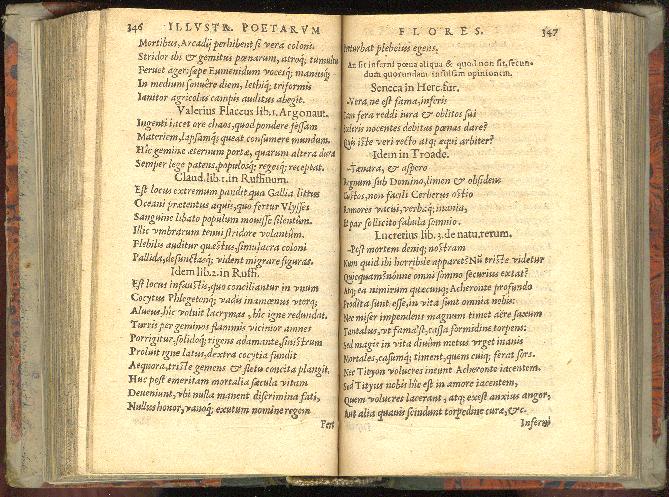

And the text of Lucretius (one serving) is reproduced on page 347, under the topic "From Inferno" and heading "An Inferni poena sit aliquo & quod non sit, secundum quorundam insulsam opinionem" (If there is any punishment in Hell, and what is not, as the foolish opinion of some):

So, you know there is nothing to fear: If we accept the view of Lucretius, Hell does not exist, we create it ourselves, in life. And if Hell existed, there is no doubt that when we get there ... be like coming home . Well, it takes as much as possible ...

Technorati tags: Epicureanism , literary topoi, hell, Lucretius, Lope de Vega , Quevedo, Lorenzo Silva , Classical Tradition

0 comments:

Post a Comment